Tuesday, March 14, 2006

TC Towers

OK, here I am living in little Traverse City, where lately a couple of developers have been moving ahead with plans to build a couple of skyscrapers in the relatively neglected West Side of Front Street. One will actually break into three digits: One hundred feet tall!

Which, of course, isn't all that big. But the very idea of a hundred foot tall building stirs up the crotchety local types (of all ages) and makes them talk about moving to the UP to get away from encroaching Babylon.

So it's a pretty sensitive subject for those who've always imagined Traverse City to be a 50s television small town.

surprisingly enough, the plans have had pretty smooth sailing through the city commission and the planning process. Partly because, apparently, some powerful parties really want to get this done.

Michael Uzelac, one of the developers of the 100-foot project, hit a snag when the developer of a somewhat smaller project nearby, proposed a cheaper alternative to the parking deck he's trying to get the city to finance as part of his project. The new proposal looks as if it can provide the same spaces for half the cost.

Why? Because Uzelac is planning on building some of his stuff ON TOP of the proposed city deck, and the deck therefore has to be built to a much higher standard to bear the load.

So why should the city be subsidizing that portion (the upper stories) of that project? Taxpayers, apparently don't deserve answers for that question. In fact they don't even deserve to know there's an alternative, because city officials and one of our state representatives did everything they could to hush up the whole prospect of an alternative.

And now, Uzelac, who had such smooth sailing through the planning process before because his plans were well-designed to ease local concerns (no, the building won't be big & ugly; no, there will be setbacks; no, we'll be providing a LOT of public parking) is going back to the planners to revise all these concessions out of his plan now that he thinks he's got an in.

Well, maybe he does: he and his associates have bought . . . um given more than $30,000 to our state senator, and he seems only too willing to use his influence to interfere in city decision making processes to make sure his sugar daddies . . . umm buddies get their way.

Which really begs the question: WHAT THE HELL IS GOING ON HERE?

Cronyism? Influence peddling?

I think it's about time someone just put the accusations out there: Jason Allen is for sale, and the entire city planning process is corrupt as the day is long, designed to railroad the projects of "friendlies" (i.e. political cronies, campaign contributors) through the process while the public isn't looking.

Anyone care to refute? The facts so far seem to fit perfectly with what I know so far, so that's how it looks. Is this what I am to think, or is there some other way to look at it?

So long as officials around here treat the public as if they are irrational idiots who have to be tricked and hoodwinked into allowing what's best for them . . . well as long as they keep us in the dark, we're free to think the worst.

And by the way, has anyone ever explained how the county contractor of this project got the contract in the first place? Cronyism? Kickbacks?

Turns out the thing collapsed, wasn't built to the appropriate code, and was lacking in essential structural elements called for in the design.

The man who investigated the debacle just happens to be the man who saw to it that they got the contract in the first place. Conflict of interest? Keeping the investigation just this side of the actual award of the contract?

You decide, but don't think you'll be doing it in a well-informed manner, fellow mushrooms.

OPK

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Kelley on Pinker on Dawkins

I've reposted the entire Times excerpt of Steve Pinker's discussion of Richard Dawkins's Selfish Gene below.

Dawkins's book was, of course, a landmark in the history of evolutionary science. With this very readable book and its more specialized companion The Extended Phenotype Dawkins scored a rare feat in the realm of science writing: explicating and popularizing a new way of looking at evolution among both popular and professional audiences.

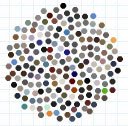

Dawkins book encouraged its readers to look at evolution with a "gene's eye" view. Thinking less about the competition between animals or bacteria, and more about the competition between different sequences of DNA. Such a view made it much easier to explain things like altuistic behavior, for instance: a brother might sacrifice his own life for his sibling and still be assured that much of his genome would get passed on to future generations. Looking at the matter this way, we can more easily see how a gene encouraging such altuistic behavior might be selected for. An entire family with this gene might survive and propagate more successfully than others over the long run, thus assuring the continued presence of the self-sacrifice gene.

While recognizing Dawkins's achievement, I many have felt that Dawkins has also had a tendency to state his claims a bit too dramatically and to push the explanatory power of his ideas a bit too far. When called out on this tendency, Dawkins has often clarified and nuanced his claims. I am someone who has been a bit skeptical of the Dawkins line of evolutionary storytelling, but I have always seen him as a very interesting and reasonable thinker with a lot to tell us about how life came to be as it is.

Steven Pinker, and cognitive scientist at Harvard and perhaps Dawkins greatest rival as a scientific popularizer, may also be Dawkins's biggest stateside comrade-in-arms. But he does not share Dawkins preference for reasonableness over drama in the final instance. Much like the postmodern theorists he has publicly deplored, Pinker often seems to prefer the romance of taking and defending an extreme position to being right.

Not that there's much danger in Pinker's posturing: like the great postmodern firebrands, he's got tenure. And his positions are not that extreme, socially. (I'd argue that they're farther from the truth that from the political mainstream.) And they're certainly not extreme enough to stem the flow of congratulation from his many fans.

The article below provides a fine example of Pinker at his worst. Aside from giving Dawkins his due praise on the 30th anniversary of The Selfish Gene, Pinker, characteristically, is also concerned to extend his thinking to new areas and new extremes:

Another shared theme in life and mind made prominent in Dawkins's writings is the use of mentalistic concepts (ie, the explanation of behaviour in terms of beliefs and desires) in biology, most boldly in his title The Selfish Gene. The expression evoked a certain amount of abuse, most notoriously in the philosopher Mary Midgley's pronouncement that "genes cannot be selfish or unselfish, any more than atoms can be jealous, elephants abstract or biscuits teleological"(a throwback to the era in which philosophers thought that their contribution to science was to educate scientists on elementary errors of logic encouraged by their sloppy use of language). Dawkins's main point was that one can understand the logic of natural selection by imagining that the genes are agents executing strategies to make more copies of themselves. . . .

The proper domain of mentalistic language, one might think, is the human mind, but its application there has not been without controversy either. . . .

I sometimes wonder, though, whether caveats about the use of mentalistic vocabulary in biology are stronger than they need to be--whether there is an abstract sense in which we can literally say that genes are selfish, that they try to replicate, that they know about their past environments, and so on. Now of course we have no reason to believe that genes have conscious experience, but a dirty secret of modern science is that we have no way of explaining the fact that humans have conscious experience either (conscious experience in the sense of raw first-person subjective awareness --the distinction between conscious and unconscious processes, and the nature of self-consciousness, are entirely tractable scientific topics). No one has really explained why it feels like something to be a hunk of neural tissue processing information in certain complex patterns. So even in the case of humans, our use of mentalistic terms does not depend on a commitment on how to explain the subjective aspects of the relevant states, but only on their functional role within a chain of computations.Mary Midgley aside, one has to wonder after reading this why philosophers ever stopped trying to "educate scientists on elementary errors of logic encouraged by their sloppy use of language." Perhaps it was despair.

Pinker's justification for using "mentalistic language" [wants, desires, knowledge] in relation to "hunks of matter" other than people and some of our animal friends is that psychology has so far failed to properly account for our sense of consciousness. So when we say an electron "wants" and a person "wants" we are referring to equally undefined phenomena.

The behaviorists responded to this by throwing mentalistic language overboard altogether. Which seems rather silly until Pinker comes up with his counterproposal: apply mentalistic language universally.

Why bother?, we might well wonder. Why not just continue to apply mentalistic language to those things that seem to us to merit such consideration, and not apply it to to things we know fairly well do not experience consciousness? Pinker himself points out several "confusions" arising out of the arbitrarily specialized use of mentalistic terms, why not just stop using them?

Speaking of cognitive psychology, Pinker tells us that mentalistic language "allows [CP] to tap into the world of folk psychology" and I think it is here that we find the true motivation behind Pinker's project here. Pinker is less concerned with overall project of understand how evolution works than he is with trying to make evolutionary storytelling attain the sort of intuitive appeal of creation myths. Pinker's project is more or less the creation of a "Wedge Strategy" on behalf of science. Much as religious belief presents itself as scientific inquiry through the work of the Discovery Institute, so Pinker's science would present itself as a story to a public much more familiar with Spielberg than with the workings of systems.

The problems here are manifold: first, this representation of how science works is contrafactual. In fact, I'd say it runs counter to the epistemological underpinnings of the scientific worldview itself. Attempts to make scientific explanations of the world appealing narratives (be they sentimental or anti-sentimental) are lies, plain and simple. [But this is too big a point to discuss completely here.]

Second, it won't work. Intelligent Design is lousy science, but it works reasonably well as a political ploy because most people can't tell the difference. Real science often makes lousy stories, and any schmo can recognize a lousy story. From the perspective of making direct appeals to the populace at large, science is in a tough spot: the only way science can be made more appealing is to make it less "real."

And that would be a bad deal, because the cultural capital of science is not going to be made by providing new grand narratives for society. Science will live or die by delivering results (where it has done fairly well) and being a reliable source of information for public decision-making (where it has done less well).

The truth of science is that there are no selfish genes. There are just different kinds of genes, some of which lead to organisms with a greater capacity to survive and propagate than others in particular environments. What lives, what dies, what propagates--these are all happenstance: the results of an extremely complex process arising out of a host of natural tendencies working in concert, with no intention behind it and no goal to achieve.

Not a heartwarming story. Not a story with great life lessons about competition and tough-mindedness. But the fundamental truth of science. Tough as it is, that's the stroy that has to be sold to converts. The public at large, though, merely has to tolerate science (and pay, of course), they don't have to practice it or even cheer from the sidelines.

OPK

Pinker on Dawkins

Centrepiece

Yes, genes can be selfish

Review by Prof. Steven Pinker

To mark the 30th anniversary of Richard Dawkins’s book, OUP is to issue a collection of essays about his work. Here, professor of psychology at Harvard University, wonders if Dawkins’s big idea has not gone far enough

The SELFISH GENE

by Richard Dawkins,

OUP £14.99, 384pp;

US television talk-show host Jay Leno, interviewing a passer-by: How do you think Mount Rushmore was formed?

Passerby: Erosion?

Leno: Well, how do you think the rain knew to not only pick four presidents — but four of our greatest presidents? How did the rain know to put the beard on Lincoln and not on Jefferson?

Passerby: Oh, just luck, I guess.

I AM A COGNITIVE SCIENTIST, someone who studies the nature of intelligence and the workings of the mind. Yet one of my most profound scientific influences has been Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist. The influence runs deeper than the fact that the mind is a product of the brain and the brain a product of evolution; such an influence could apply to someone who studies any organ of any organism. The significance of Dawkins’s ideas, for me and many others, runs to his characterisation of the very nature of life and to a theme that runs throughout his writings: the possibility of deep commonalities between life and mind.

Dawkins’s ideas repay close reflection and re-examination, not because he is a guru issuing enigmatic pronouncements for others to ponder, but because he continually engages the deepest problems in biology, problems that continue to challenge our understanding.

When I first read Dawkins I was immediately gripped by concerns in his writings on life that were richer versions of ones that guided my thinking on the mind. The parallels concerned both the content and the practice of the relevant sciences.

A major theme in Dawkins’s writings on life that has important parallels in the understanding of the mind is a focus on information. In The Blind Watchmaker Dawkins wrote: “If you want to understand life, don’t think about vibrant, throbbing gels and oozes, think about information technology.” Dawkins has tirelessly emphasised the centrality of information in biology — the storage of genetic information in DNA, the computations embodied in transcription and translation, and the cybernetic feedback loop that constitutes the central mechanism of natural selection itself, in which seemingly goal-oriented behavior results from the directed adjustment of some process by its recent consequences. The centrality of information was captured in the metaphor in Dawkins’s book title River Out of Eden, the river being a flow of information in the generation-to-generation copying of genetic material since the origin of complex life. It figured into his Blind Watchmaker simulations of the evolutionary process, an early example of the burgeoning field of artificial life. Dawkins’s emphasis on the ethereal commodity called “information” in an age of biology dominated by the concrete molecular mechanisms is another courageous stance. There is no contradiction, of course, between a system being understood in terms of its information content and it being understood in terms of its material substrate. But when it comes down to the deepest understanding of what life is, how it works, and what forms it is likely to take elsewhere in the universe, Dawkins implies that it is abstract conceptions of information, computation, and feedback, and not nucleic acids, sugars, lipids, and proteins, that will lie at the root of the explanation.

All this has clear parallels in the understanding of the mind. The “cognitive revolution” of the 1950s, which connected psychology with the nascent fields of information theory, computer science, generative linguistics and artificial intelligence, had as its central premise the idea that knowledge is a form of information, thinking a form of computation, and organised behaviour a product of feedback and other control processes. This gave birth to a new science of cognition that continues to dominate psychology today, embracing computer simulations of cognition as a fundamental theoretical tool, and the framing of hypotheses about computational architecture (serial versus parallel processing, analogue versus digital computation, graphical versus list-like representations, etc) as a fundamental source of experimental predictions.

Another shared theme in life and mind made prominent in Dawkins’s writings is the use of mentalistic concepts (ie, the explanation of behaviour in terms of beliefs and desires) in biology, most boldly in his title The Selfish Gene. The expression evoked a certain amount of abuse, most notoriously in the philosopher Mary Midgley’s pronouncement that “genes cannot be selfish or unselfish, any more than atoms can be jealous, elephants abstract or biscuits teleological” (a throwback to the era in which philosophers thought that their contribution to science was to educate scientists on elementary errors of logic encouraged by their sloppy use of language). Dawkins’s main point was that one can understand the logic of natural selection by imagining that the genes are agents executing strategies to make more copies of themselves. This is very different from imaging natural selection as a process that works toward the survival of the group or species or the harmony of the ecosystem or planet. Indeed, as Dawkins argued in The Extended Phenotype, the selfish-gene stance in many ways offers a more perspicuous and less distorting lens with which to view natural selection than the logically equivalent alternative in which natural selection is seen as maximising the inclusive fitness of individuals. Dawkins’s use of intentional, mentalistic expression was extended in later writings in which he alluded to animals ’ knowing or remembering the past environments of their lineage, as when a camouflaged animal could be said to display a knowledge of its ancestors’ environments on its skin.

The proper domain of mentalistic language, one might think, is the human mind, but its application there has not been without controversy either. During the reign of behaviourism in psychology in the middle decades of the 20th century, it was considered as erroneous to attribute beliefs, desires, and emotions to humans as it would be to genes, atoms, elephants or biscuits. Mentalistic concepts, being unobservable and subjective, were considered as unscientific as ghosts and fairies and were to be eschewed in favour of explaining behaviour directly in terms of an organism’s current stimulus situation and its past history of associations among stimuli and rewards. Since the cognitive revolution, this taboo has been lifted, and psychology profitably explains intelligent behaviour in terms of beliefs and desires. This allows it to tap into the world of folk psychology (which still has more predictive power when it comes to day-to-day behaviour than any body of scientific psychology) while still grounding it in the mechanistic explanation of computational theory.

In defending his use of mentalistic language in biological explanation, Dawkins has been meticulous in explaining that he does not impute conscious intent to genes, nor does he attribute to them the kind of foresight and flexible cleverness we are accustomed to in humans. His definitions of “selfishness”, “altruism”, “spite”, and other traits ordinarily used for humans is entirely behaviouristic, he notes, and no harm will come if one remembers that these terms are mnemonics for technical concepts rather than direct attributions of the human traits.

I sometimes wonder, though, whether caveats about the use of mentalistic vocabulary in biology are stronger than they need to be — whether there is an abstract sense in which we can literally say that genes are selfish, that they try to replicate, that they know about their past environments, and so on. Now of course we have no reason to believe that genes have conscious experience, but a dirty secret of modern science is that we have no way of explaining the fact that humans have conscious experience either (conscious experience in the sense of raw first-person subjective awareness — the distinction between conscious and unconscious processes, and the nature of self-consciousness, are entirely tractable scientific topics). No one has really explained why it feels like something to be a hunk of neural tissue processing information in certain complex patterns. So even in the case of humans, our use of mentalistic terms does not depend on a commitment on how to explain the subjective aspects of the relevant states, but only on their functional role within a chain of computations.

Taking this to its logical conclusion, it seems to me that if information-processing gives us a good explanation for the states of knowing and wanting that are embodied in the hunk of matter called a human brain, there is no principled reason to avoid attributing states of knowing and wanting to other hunks of matter. To be specific, nothing prevents us from seeking a generic characterisation of “knowing” (in terms of the storage of usable information) that would embrace both the way in which people know things (in their case, in the patterns of synaptic connectivity in brain tissue) and the ways in which the genes know things (presumably in the sequence of bases in their DNA). Similarly, we could frame an abstract characterisation of “trying” in terms of negative feedback loops, that is, a causal nexus consisting of repeated or continuous operations, a mechanism that is sensitive to the effects of those operations on some state of the environment, and an adjustment process that alters the operation on the next iteration in a direction, thereby increasing the chance that that aspect of the environment will be caused to be in a given state. In the case of the human mind, the actions would be muscle movements, the effects would be detected by the senses, and the adjustments would be made by neural circuitry programming the next iteration of the movement. In the case of the evolution of genes, the actions would be extended phenotypes, the effects would be sensed as differential mortality and fecundity, and the adjustment would be made in terms of the number of descendants resulting in the next generation.

This characterisation of beliefs and desires in terms of information rather than physical incarnation may overarch not only life and mind but other intelligent systems such as machines and societies. By the same token it would embrace the various forms of intelligence implicit in the bodies of animals and plants, which we would not want to attribute either to fully human cogitation nor to the monomaniacal agenda of replication characterising the genes. When the coloration of a viceroy butterfly fools the butterfly’s predators by mimicking that of a more noxious monarch butterfly, there is a kind of intelligence being manifest. But its immediate goal is to fool the predator rather than replicate the genes, and its proximate mechanism is the overall developmental plan of the organism rather than the transcription of a single gene.

In other words the attribution of mentalistic states such as knowing and trying can be hierarchical. The genes, in order to effect their goal of making copies of themselves, can help to build an organ whose goal is to fool a predator. The human mind is another intelligent mechanism built as part of the intelligent agenda of the genes, and it is the seat of a third (and the most familiar) level of intelligence: the internal simulation of possible behaviours and their anticipated consequences that makes our intelligence more flexible and powerful than the limited forms implicit in the genes or in the bodies of plants and animals. Inside the mind, too, we find a hierarchy of sub-goals (to make a cup of coffee, put coffee grounds in the coffeemaker; to get coffee grounds, grind the beans; to get the beans, find the package; if there is no package, go to the store; and so on).

Computer scientists often visualise hierarchies of goals as a stack, in which a program designed to achieve some goal often has to accomplish a sub-goal as a means to its end, whereupon it “pushes down” to an appropriate sub-routine, and then “pops” back up when the sub-routine has accomplished the sub-goal. The sub-routine, in turn, can call a sub-routine of its own to accomplish an even smaller and more specialised sub-goal. (The stack image comes from a memory structure that keeps track of which sub-routine called which other sub-routine, and works like a spring-loaded stack of cafeteria trays.) In this image, the best laid plans of mice and men are the bottom layers of the stack, and above them is the intelligence implicit in their bodies and genes, with the topmost goal being the replication of genes that makes up the core of natural selection.

It would take a good philosopher to forge bulletproof characterisations of “intelligence”, “goal”, “want”, “try”, “know”, “selfish”, “think”, and so on, that would embrace minds, robots, living bodies, genes and other intelligent systems. (It would take an even better one to figure out how to reintroduce subjective experience into this picture when it comes to human and animal minds.) But the promise that such a characterisation is possible — that we can sensibly apply mentalistic terms to biology without shudder quotes — is one of Dawkins’s legacies. If so, we would have a deep explanation of our own minds, in which parochial activities like our own thinking and wanting would be seen as manifestations of more general and abstract phenomena.

The idea that life and mind are in some ways manifestations of a common set of principles can enrich the understanding of both. But it also mandates not confusing the two manifestations — not forgetting what it is (a gene? an entire organism? the mind of a person?) that knows something or wants something, or acts selfishly. I suspect that the biggest impediment to accepting the insights of evolutionary biology in understanding the human mind is in people’s tendency to confuse the various entities to which a given mentalistic explanation may be applied. One example is the common tendency to assume that Dawkins’s portrayal of “selfish genes” implies that organisms in general, and people in particular, are ruthlessly egoistic and self-serving. In fact nothing in the selfish-gene view predicts that this should be so. Selfish genes are perfectly compatible with selfless organisms, since the genes’ goal of selfishly replicating themselves can be implemented via the sub-goal of building organisms that are wired to do unselfish things such as being nice to relatives, extending favors in certain circumstances, flaunting their generosity in other circum- stances, and so on. (Indeed much of The Selfish Gene consists of explanations of how the altruism of organisms is a consequence of the selfishness of genes.) Another example of this confusion is the claim that socio-biology is refuted by the many things people do that don’t help to spread their genes, such as adopting children or using contraception. In this case the confusion is between the motive of genes to replicate themselves (which does exist) and the motive of people to spread their genes (which doesn’t). Genes effect their goal of replication via the sub-goal of wiring people with goals of their own, but replication per se need not be among those sub-sub-goals: it’s sufficient for people to seek sex and to nurture their children. In the environment in which our ancestors were selected, people pursuing those goals automatically helped the relevant genes to pursue theirs (since sex tended to lead to babies), but when the environment changed (such as when we invented contraception) the causal chains that used to make sub-goals bring about superordinate goals were no longer in operation.

Edited extract from Richard Dawkins: How a Scientist Changed the Way We Think edited by Alan Grafen and Mark Ridley, published on March 16 by OUP, £12.99, offer £11.69 (in p&p)

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Couple of cool science blogs

The site that recommended hpb to me is also worth checking out: Gene Expression is a less formal blog dealing with many of the same issues, with contemporary social events and religion often cropping up as well.

OPK

Monday, January 30, 2006

More on Seed

This, I thought, was very well-reasoned. Unfortunately, the Seed folks would never give it a moment's thought because it comes from a quarter they regard as "politicized."

Seeds of Doubt

by Brandon Keim

One of the more interesting publications to debut in recent years is SEED, a slickly produced magazine founded with the intention of exploring, in their words, the "trends and icons that are redefining science's place in popular culture." In practice, this means a determinedly edgy editorial aesthetic and lots of artsy black-and-white photographs of skinny models in designer jeans and tight shirts.

SEED’s editors certainly have a keen sensibility for the permeation of our lives by the products and ideas of science, and a knack for making them accessible to the 18 to 34 year old demographic upon whom the hopes of society's marketers are bestowed, and whose tastes and views constitute the popular culture of our youth-driven society. It was thus a matter of particular interest when, in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the 'discovery' of DNA's three-dimensional structure, James Watson made an appearance on the cover of SEED’s March/April edition.

In the photograph, Watson relaxes on a stool in front of a studio photographer's screen, ostensibly in the moments before the shoot begins; he is attended by a fetching blonde makeup artist in leather pants, and on the floor before him is a sycophantic young man gazing reverentially upwards. The image is insightful. Watson is, and has almost always been, far less of a scientist than a proselytizer, a salesman — an icon. Unfortunately, one of SEED's flaws is an unquestioning acceptance of the logic of celebrity, and the suspension of critical rigor towards those who have attained it. Readers are treated to a typically glowing account of Watson, one which focuses with some insight on the phenomenon of his celebrity and self-promotion, but leaves untouched both the origins of his sucess and the actual science upon which his career — and, simultaneously, modern genetics — was founded.

The standard mythology of Watson and Crick, repeated consistently during the anniversary coverage, venerates them as a pair of visionary micronauts, a Lewis and Clark of the cell. However, a number of their colleagues deserved just as much credit — most prominently, Rosalind Franklin, whose x-ray photographs of DNA defined the shape of the double helix,

and researchers at King's College in London, who suggested that the strands of the helix ran in opposite directions. Without them, and without the repeated corrections of patient and forbearing colleagues, the efforts of Watson and Crick would have gone nowhere.

Of course, their 'achievements' would not have been rewarded with half a century of the highest honors our civilization offers without the disproportionate importance subsequently attributed to DNA — its endowment "with mystical powers like the narcotic soma of Hindu ritual". So

wrote Richard Lewontin, a contributor to this issue, in a recent New York Review of Books commentary on Watson's latest book.

These "narcotic" effects are efficiently summarized in SEED’s thematic centerpiece, a list of fifty DNA-based ideas "that have shaped our identity, our culture and the world as we know it." The first item on the list, entitled "The New Soul", explains that "'Soul' is being ousted from our lexicon by 'DNA' as the new and improved tag for that ethereal x-factor." Following the dismissal of our spiritual self-conception is a wildly inaccurate description of prenatal genetic testing as a "crystal ball" of uncontested clarity; the claim that "understanding DNA may one day allow us to write our genetic future"; an assertion that an avant-garde portrait composed of DNA provides "instructions on how to remake the sitter"; and the bizarre statement that the "dominant alphabet" of the human race "is changing from 1s and 0s" of computer coding "to As, Ts, Cs and Gs".

All in all, it's a comprehensive review of genetic reductionism — what Stuart Newman, who in this issue discusses how the once-fertile area of systems biology was ignored because of our obsession with genes, calls "the twentieth century notion that genes represent a privileged level of explanation." He is joined by the aforementioned Mr. Lewontin, who examines the underappreciated complexity of cellular machinery and delivers a stinging indictment of genetic manipulation's failures. Taken together, and in conjunction with the critique of so-called DNA self-replication, put forward in our last issue by Barry Commoner, they are welcome counters to the scientific and popular misconceptions that have been repeated so frequently of late.

But while the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of DNA's discovery are, like all such nniversaries, rituals of immediate focus, they also encourage us to contemplate the scope of history and time, especially in regard to science; and there is nothing so common in the history of science as universal theories which rise to prominence and are soon swept away, the contributions of their advocates placed in proper perspective. In another fifty years, perhaps, we will say the same of Watson and Crick, and the importance that is now ascribed to our contemporary notions of genetics.

Monday, January 23, 2006

Seed magazine & scienceblogs

Back to Seed Magazine. My comment about Seed "trying too hard to be hip" is actually a big caveat for me. This problem goes to the identity of the magazine.

The purpose of the magazine, it seems to me, is to help build a community of the scientifically literate.

But the effort seems destined to fail if they envision that happening through a magazine that one commenter called "a Maxim for science."

Maxim is essentially a well-done magazine for male morons. What lessons is Seed supposed to draw from this quarter?

And it isn't that the commentator who brought up Maxim is off-base. He has identified precisely what the problem with the magazine is: it's trying to bring together an intellectual community with an anti-intellectual instrument. The contradiction is written all over the magazine.

The thing is that what they're trying to pull off hasn't been done before. To my knowledge, there has never been a widely accepted voice for/by/of the scientifically literate. What Maxim pulled off was easy by comparison: cut the claptrap and give 'em some cleavage. A time-honored formula that need only be updated.

How do you properly make science seem "cool and relevant and edgy?"

My first suggestion would be to not make ostentatious efforts to be cool and relevant and edgy. Go for simple, straightforward and minimalistic. Don't overcommit to any particular field of study, group of people or style. Be true to the scientific spirit and experiment in an open-ended fashion. In other words: feel your way forward.

And, for God's sake, don't run long articles with big blocks of text faced by incredibly distracting graphics, or intersperse various textual elements randomly with graphics. Short attention spans may be something you have to live with, but you shouldn't be in the business of enforcing them.

These are all lesson already learned by Wired. And Seed doesn't have the luxury of repeating those mistakes. Wired had a lot of dumbass millenarianism behind it (remember cyber____, e____ and virtual ______ till you were ready to barf?).

Seed and science will have to show their relevance not just reap the rewards of irrational exuberance. So away with the trappings of pseudo-hipness and cut to the stories that will change the way people think about the world. Away with the Steven Pinker worship and let's have let's have some hard, critical looks at science.

Let the trappings grow up organically out of the core concerns of the magazine. You are building a culture not a clique.

Will Seed be able to pull it off? Maybe. But it's going to take some truly daring modesty and caution.

Science itself has been hurt of late by some of the same tendencies toward shallowness and showiness Seed has displayed, and the troubles surrounding evolution are what we reap from this.

For instance, much evolutionary psychology is, quite simply, bad science, and it's been long tolerated because it takes natural selection as a given. But it is long since past time that science stopped counting the display of appropriate allegiance as a scientific credential. Science should be, first and foremost, a highly self-critical endeavor. So far, Seed gives little reason to think that'll happen in its pages.

OPK

Saturday, January 21, 2006

Scienceblogs!

Seed looks to be an outgrowth of the whole "Third Culture" movement (which you can check out at The Edge).

So far, the magazine has tried a bit too hard to be hip, and has been a bit too chummy and cogratulatory with the scientists the Edge folk have always been happy with (Stephen Pinker, for instance), and a bit too self-congratulatory it taking up its enlightened social position.

But the blogs may lead to something a bit more open, and quite a bit better, more later.

Thursday, December 15, 2005

Literary Theory in Crisis. yawn

Either literary theory is dead, or it's invincible. It all depends on who's talking. When Jacques Derrida died last year, The New York Times declared the end of the era of "big ideas." In April 2003, the Times had run an article about a University of Chicago symposium on the state of theory headlined "The Latest Theory Is Theory Doesn't Matter." More recently, a November 17 essay in the online magazine Slate mourned "The Death of Literary Theory."

Others say that theory has never been more perniciously alive. These critics persist in arguing that it is no longer possible to study literature for its own sake.

Just this summer, Columbia University Press published Theory's Empire: An Anthology of Dissent. The volume collects 30 years' worth of contrarian arguments with theory — make that Theory with a capital T — and takes as its premise the notion that "the rhetoric of Theory has been successful in gaining the moral and political high ground, and those who question it do so at their peril."

A long article in the current Chronicle of Higher Education (the college and university trade mag) on "What Happened" to literary theory. As someone who actually studied this stuff fairly seriously back in my college days, I have to wonder, "Who the hell cares?"

I mean, we might just as well spend our time worrying about the crisis in pigeon fancying for all it means even to me--someone who has actually read (God help me) Derrida and De Man and Baudrillard and Barthes. Someone who knows the name Shoshana Felman and has some idea what she's about. Someone who is not particularly scandalized by anything these folk have to say. Even I am utterly indifferent to literary theory and its possibly being in a crisis.

Of course, I no longer have any direct involvement in the field, but any field that has no importance to anyone not directly involved should seriously think about pigeon fancying and why the government doesn't give comparable funding to that hobby.

The only thing one is inspired to wonder reading this Chronicle piece is "Why are we paying people to research this stuff?"

Well, no that's wrong, one might also wonder "Why are we requiring students to study this stuff?"

It's hard for me not to look on people who still tool away at this stuff as nothing more than thieves of education funding that would be far better spent on primary school kids. But maybe that's just me.

OPK

Monday, December 12, 2005

Evil: David Brooks on Munich

Brooks, like most conservative pundits, likes to come off as a hard-headed fellow, not one to be put off the game by misty abstractions. But, on the other hand, he insists on using, and on other people using, a term which I'm betting he has no definition for: evil.

Spielberg's film is centered on the terrorist murder of 10 Israelis and one American at the 1972 Munich Olympics, and the reprisals that arose from it. Spielberg uses these events as a springboard to deal with larger issues like the Arab/Israeli conflict more generally, and perhaps all seemingly intractable human conflicts.

Brooks seems to think the film is well-done, but he has a major complaint with the world-view behind it. Brooks contends that by setting the film in 1972, Spielberg can avoid acknowledging and dealing with "evil," which for Brooks is embodied in radical Islamic groups like Islamic Jihad and Hamas.

Setting aside the question of whether the 1972 terrorists are any more sympathetic than 2002 terrorists, one has to remark at how many conservative commentators today seem to hold up the acknowledgement of evil as the sine qua non of realistic discussion of practically any issue.

I find quite the opposite to be the case. "Evil" is generally used, like Brooks uses it, as an empty signifier which the reader may insert whatever he or she most fears in the context in which it is used. And generally speaking, whenever we hear someone going on about "evil" in a foreign or public policy debate, we are sure to hear all sorts of speculation, contrafact and pure fantasy from the same source.

Take our president for example: he starts off warning us of the (cue reverb) "Axis of Evil," and soon enough we're hearing about chemical weapons stockpiles, yellowcake buys, dire threats to American well-being, rose-petal-strewn streets, quickly returning American GIs, etc., etc.

Well, we know how all that turned out.

What we should really hear when we hear a policy wonk say "evil" is "I am attempting to justify what I fear I cannot otherwise justify by making reference to this shibboleth. Surely you aren't heretic or heathen enough to keep questioning me now!"

Mr. Brooks' article shows every indication that he has not the least notion of what he means when he says "evil." Of course, he can identify certain parties who are evil (radical Islam), but can he tell us what evil is more generally? I doubt it.

For instance, Brooks points out that one of Spielberg's terrorists makes a speech which "sounds like Mahmood Abbas," implying that somehow this makes for a sympathetic villain. But Abbas is the head of an organization (the PLO) which has killed innocents by the score, including those Olympic athletes, sometimes with sickening arbitrariness and viciousness. Not so long ago it was the PLO which led the list of the "evil" organizations that could only be eliminated, not negotiated with. Now their leader is the model for sympathetic insurrection?

On the other hand, hard-headed Brooks tells us that Spielberg's refusal to acknowledge evil means he gets his Israeli hero wrong, too. Far from being the conscience-ridden hero of Spielberg's film, real Israeli assassins are "less sympathetic" and "hard." Hard enough, one wonders, to kill or torture innocents? I think we already know the answer to that. You gotta crack some eggs and all that. There's probably an Arabic equivalent to that expression.

Are those Israelis really heroes? Or are they evil? Or is the small evil they do OK because it is done to benefit a larger, good, cause. But Bin Laden thinks he has a good cause, too, doesn't he?

And if, as Brooks implies at another point, evil is to be measured by one's intransigence, what are we to think of the zealots on the Israeli right, who don't really keep much of a secret of their determination to eliminate all those who oppose their vision of Zion. Are they evil?

My answer is "maybe" and "from a policy perspective, who cares?" The thing about evil and extremism is that it is everywhere: we've got extremists in the US, they're there in Israel, and they are amongst the Palestinians. In fact, we can probably just go along with what many Christian philosophers say and agree that all of us harbor evil in our hearts. The trick is to not let it get the upper hand: to rue the small evils that we do and to always be uncertain of the great goods we expect to arise from them. And most of all, perhaps, not to justify our own actions because our enemy is "evil" and anything we do against him is therefore acceptable. That is fairly close to the philosophy of the Bin Ladens.

The big trouble with the Palestinians and much of the Arab world is that extremism (or, if you insist, "evil") is not under control, as it generally is in the US and Israel. But this doesn't mean that those societies are inherently evil, or that we should never make any compromise with any of them. It means that we have to start trying to create the conditions under which consensus in those societies moves away from the extreme, where the populace will be less willing to look the other way or tacitly approve when they encounter atrocities, where extremism will pose a threat to them as well. In short, we have to give these people something they value which they might lose, we have to give the moderate less excuse to see us as evil, and we have to stop giving ourselves excuses to act out evil ourselves.

Our problem, though, is not our failure to acknowledge evil, it is the fact that we use it too much. We use the word evil when we want to leave our own motives unexamined; we use it when we want to ignore the legitimate grievances of others; and we use it when we want to justify our own evil acts.

I am far, far from saying that America is itself "Evil." I think that would be a stupid thing to say regardless of what we might be doing. I think we are the "good guys." I, for one, love this country enough that I do not have to lie and obfuscate to justify that love--I can love us imperfect as we are. But I think nothing is gained by idealizing either ourselves or our enemies. Let's have a cold honest look at ourselves and our situation and do what's needed to win. And let us, please, dispense with the childish need for unambiguous heroes and unambiguous villains so long and so assiduously cultivated in us by Mr. Spielberg and his Hollywood colleagues.

Mr. Brooks, it's time to grow up, forget about the boogie man, and face up to the ugly task of fighting a real, human conflict. It's time to let "evil" be a greater part of our private reflections and a much lesser part of our sometimes fatuous public discourse on the war.

OPK

Friday, December 09, 2005

Sprawl? Good?

ARCHITECTURE

Sprawling into controversy

Professor and author Robert Bruegmann is defying conventional wisdom with his claim that suburban creep is both an ancient phenomenon and a beneficial one.

By Scott Timberg

Times Staff Writer

December 9, 2005

Professor and author Robert Bruegmann is defying conventional wisdom with his claim that suburban creep is both an ancient phenomenon and a beneficial one. At first glance, Robert Bruegmann --— a childless academic whose modernist apartment building sits in a dense, upscale Chicago neighborhood --— seems like the kind of guy who'd hate the suburbs. His peers and predecessors have, for decades, decried the unplanned, low-density, auto-dependent growth of shopping malls and subdivisions.

But he's emerging as the unlikely champion of what we've called, at least since the 1950s, "sprawl." His counterintuitive new book, "Sprawl: A Compact History," charts the spreading of cities as far back as 1st century Rome, and finds the process not just deeply natural but often beneficial for people, societies and even cities.

The Boston Globe has called Bruegmann "the Jane Jacobs of suburbia," after the urban historian who celebrated the serendipitous, high-density warren of Greenwich Village and other old neighborhoods.

"Sprawl has been as evident in Europe as in America," he writes, "and can now be said to be the preferred settlement pattern everywhere in the world where there is a certain measure of affluence and where citizens have some choice in how they live."

Debates over sprawl and urbanism tend to be very emotional and morally tinged to the point of moralism. Another new book, Joel S. Hirschhorn's "Sprawl Kills: How Blandburbs Steal Your Time, Health and Money," blames sprawl not only for social isolation but also for traffic accidents and untimely death caused by sedentary lifestyles. On the other side of the aisle, libertarians often excoriate sprawl's opponents as uptight liberal "elitists."

Though Bruegmann--a professor of art history, architecture and urban planning at the University of Illinois at Chicago-- is making a bold, even contrarian argument, he discusses it with an art historian's detachment.

Bruegmann has always been interested in the built environment and urban change. "When I went to study this," he says by phone from Chicago, "I went to a department of art history, because that's where people talked about architecture. It probably wasn't the most logical place for me to go, because when I got there I had to learn about Nativity scenes and the Madonnas of 15th century Florence.

"However, it gave me something that I think is invaluable: a broad panorama of what people have thought about aesthetics over the last couple of thousand years. And because a lot of social scientists don't have that, they're often very puzzled by arguments that truly are aesthetic and metaphysical in nature but are disguised as being pragmatic and about objective things."

He's a historian of the beautiful, documenting something often taken as the height of ugliness. And the issue, he says, really is aesthetic at base. "And aesthetic judgments are not very susceptible to explanation or argument. That's why it's so hard to talk about."

Part of what's startling about the book is its defiance of the idea that sprawl was birthed in the postwar U.S.: Sprawl is not just bad but "American bad," architecture critic Witold Rybczynski writes in a recent Slate review, blaming it, with tongue in cheek, for everything from McMansions to the disappearance of countryside to an oil-driven Gulf War. "Like expanding waistlines, it's touted around the world as an example of our profligacy and wastefulness as a nation."

But Bruegmann's book is grounded in a history lesson--one that finds the roots of present-day Houston, Atlanta and Los Angeles in Augustan Rome or Restoration London. People of means, he writes, have always tried to get some distance from urban centers, often inhabiting villas outside city walls.

"I'm sure you would have found it in the very first city ever established," he says. "Living in cities has almost always been unpleasant and unhealthy--not something most people wanted. If you were in imperial Rome, crowded into dark, dingy, polluted apartment buildings, it would have been a nightmare. Most cities I looked at had just crushing density until about the 18th century."

In the Middle Ages, most cities in continental Europe had walls to protect them from wars and invasions, keeping them concentrated and providing relatively sharp distinctions between the city proper and the suburbium, as Romans called it, outside.

But a quirk of geography, and the nation's early-modern political unity, led London to become the first metropolis to sprawl massively. The fact that Britain was surrounded by water protected its capital from foreign invaders, so the city stretched beyond its medieval walls as nobles and burghers built country palaces in once-distant western reaches now woven into the city's fabric. As London became Europe's most populous and dynamic city, it grew horizontally.

Like London, whose unchecked growth was denounced by the intellectuals of its day, Los Angeles was deemed a sprawling, tacky, man-made disaster. Norman Mailer, for instance, described the "pastel monotonies of ... Los Angeles' ubiquitous acres ... built by television sets giving orders to men."

But L.A. was on its way to becoming highly dense, and greater L.A. is now, at more than 7,000 people per square mile, the densest urban area in the United States. (Unlike most East Coast cities, even L.A.'s outlying areas are very tightly packed.)

"Los Angeles is the most staggering thing," Bruegmann says of the city's vertical growth since the early '70s. Since then, he says, cities like San Francisco, L.A. and San Diego have become what he calls "hyper-versions of the rest of the country."

And while the traffic, pollution and housing prices may dismay residents, Bruegmann insists that "the problem of Los Angeles is the problem of success: It's become so attractive that everyone wants to live there." And it's done this, he says, without paying the environmental and aesthetic price of more wide-open cities like Atlanta and Houston.

By contrast, he argues, the "smart growth" policies of Portland, Ore., have been ambiguous. Portland is eminently livable but has not reduced sprawl and remains a low-density city. As its density starts to climb, he says, housing prices are going up.

One of his most shocking assertions is that suburban spread helps cities and their urban centers: Look at the way immigrants and the poor moved out of Lower Manhattan, for instance, only to have the area later reborn as a chic living space for artists and young people. It wouldn't have happened, he argues, if the highways and houses beyond the city center hadn't siphoned off population, allowing these neighborhoods to be reborn.

Even fans of Bruegmann's book blanched at this notion.

"It's certainly true that deindustrialization of any downtown presents some opportunities," author and journalist Alan Ehrenhalt wrote in an approving review in the trade magazine Governing. "But for every inner-city district that has emptied out and retooled, many more have been emptied out and are waiting desperately for the revival to begin. Abandonment is an awfully high price for the chance to start over. I wouldn't expect the leadership of Detroit or St. Louis to find Bruegmann's long view of urban history very consoling."

But Bruegmann points at downtown L.A., where he sees this process, despite some rough years, bearing fruit.He has some emotional sympathy with anti-sprawl critics, just as he does with environmentalists. But he thinks both groups are a little shortsighted when it comes to the real costs of their programs.

"By trying to stop sprawl, you'll be doing something very beneficial to the incumbents' club," he says. "It stops change and makes it harder for people to get onto the middle-class ladder. It has a definite effect on social and economic mobility."

Sprawl may not be inevitable, but it is, he says, "completely essential" to the functioning of a free society. "It goes absolutely to the heart of people's aspirations--— what it is they want to be, of how they want to live," Bruegmann says. "And tampering with that is very, very fraught."

If you want other stories on this topic, search the Archives at latimes.com/archives.

This is interesting. I'm no big fan of abandoned cities or low-density stripmalldom, but the idea that change has to happen, and that this sort of moving about is the best way to get it done is an interesting proposition. A lot of folks who are against sprawl seem very little concerned with change, or things like inexpensive, convenient housing, or things like startup businesses.

This point-of-view is more or less an intelligent articulation of the seemingly mindless growth boosterism one often runs into at the local chamber of commerce. Maybe it's not really so mindless.

While we may not agree that sprawl is good, we may agree that some of the things thatfacilitatesltitates are good, and that plgovernmentsernemnts and environmentalists ought to be thinking about them.

Follow link to an exerpt from Bruegmann's book. Thanks to Dean.

OPK

Here's one way to get a committee off the dime

Transportation group offered incentive

State offers money if group takes some action

By BRIAN McGILLIVARY

Record-Eagle staff writer

TRAVERSE CITY - The state of Michigan is dangling $25,000 before a local transportation study group to jump-start a process several members acknowledge is stalled.

"We're starting to hear grumbling in the community that (we) aren't doing anything," said Ken Kleinrichert, a member of the Land Use and Transportation Study group. "People are losing interest."

Eight months after their appointment to study and recommend a long-term remedy to the region's burgeoning transportation woes, the 29-member group has failed to agree on the scope of work they want studied or how the study should be designed and implemented.

A proposal mandating that a timeline be in place by February for hiring a consultant was defeated Tuesday by a lone member.

Under the proposal, if the timeline is missed, TC-TALUS, the governmental organization responsible for spending up to $3.3 million in federal money on the study, would create the schedule.

"If we have a group that can't even put together a timeline, then TC-TALUS steps in and sets it," Kleinrichert said. "Otherwise, we are going to go in circles for the next five years."

Ken Smith of the Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council objected to TC-TALUS directing the group.

"If we can't be accountable to ourselves, then why do we have to have TC-TALUS tell us," Smith said.

The Michigan Department of Transportation said it will authorize $25,000 for TC-TALUS to hire attorney Robert Grow to coach the transportation group to design its study process and hire a consultant.

"They've been at this for quite some time and we haven't seen any movement," said David Langhorst of MDOT. "We're looking to make something happen and this is a good way to do it."

Grow, co-founder of Envision Utah, a nationally recognized regional planning effort, spoke recently at a retreat for the Traverse City Area Chamber of Commerce.

Members of the LUTS group and MDOT said Grow impressed them.

What's still to be determined, though, is if Grow is interested.

Langhorst said if Grow doesn't take the job the LUTS group needs to find someone like him.

"I believe this will be money well spent," Langhorst said. "We have a special opportunity here and we should take it."

© Traverse City Record-Eagle

The Land Use and Transportation Study group is an interesting study in how NOT to do inclusiveness. This is a group that includes every elected official imaginable as well as a bunch of unelected and unaccountable representatives from groups like the Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council.

Nothing against the groups, but they belong on the outside of decision-making bodies, not on the inside. No one elected these folks, and they shouldn't be deciding the transportation future of the region, especially when some of them seem to perceive their role on the transport committee as making sure nothing happens. I don't think any more government money need be spent buying these people off.

Whatever the committee decides on, there will be lawsuits filed. So long as people give money to support groups whose sole purpose is filing obstructionist lawsuits, there will be obstructionist lawsuits.

There's been a lot of complaining from the paper (and other folks up here) about how secretive and non-participatory government can be up here. But letting in more special interest groups IS NOT the answer. The answer is being open to the public at large, and justifying your actions to the public at large. Right now the public interest is basically being held hostage by conflicting interest groups. It's time to kick them off the committee and let the elected public representatives do their business.

OPK

Monday, December 05, 2005

Google and Books

George Dyson on Google book scanning: "The Universal Library"

excerpt from an essay by George Dyson on edge:

Digital coding is the universal language allowing free translation between abstract information and physical books. Once upon a time, if you wanted the information, you had to physically possess (or borrow) the book. If you wanted to purchase a new copy of the book, the title had to be "in print."

This is no longer true. Scan the text once, digitally, and the information becomes permanently available, anywhere, no matter what happens to physical copies of the book. Search for an out-of-print title and you will now find bookshops (and libraries) who have copies available; soon enough the options will include bookshops offering to print a copy, just for you. Google Library and Google Print have been renamed Google Book Search--not because Google is shying away from building the Universal Library (with links to the Universal Bookstore) but because search comes first. To paraphrase Tolkien: "One ring to find them, one ring to bind them, one ring to rule them all."

Why does this strike such a nerve? Because so many of us (not only authors) love books. In their combination of mortal, physical embodiment with immortal, disembodied knowledge, books are the mirror of ourselves. Books are not mere physical objects. They have a life of their own. Wholesale scanning, we fear, will strip our books of their souls. Works that were sewn together by hand, one chapter at a time, should not be unbound page by page and distributed click by click. Talk about "snippets" makes authors flinch.

I am . . . what? fascinated? puzzled? flabberghasted? by the response to the whole Google Books project.

Seemingly intelligent people are taking up stances that make no sense whatsoever, or ones that seem to run directly contrary to their own interests. George Dyson, for instance. I imagine he's a smart guy. And I love books, too. But everything what he's written on Google of late (this piece and "Turing's Cathedral," available at The Edge) seem almost unbelievablyy beside the point. Yes books are physical objects. So what?

The reaction to Google's ambition to index everything bears a lot of similarity to the popular-intellectual response to cyberpunk writing and the emergence of the Internet.Rememberr all the half-informed drivel written about something called "cyber space" which was going to replace all genuine, authentic experience with a simulation. Luckily, somehow that didn't happen.

New media and the availability of new ways to use new media do not spell the disappearance of old media and old ways. Mr. Dyson and book lovers everywhere (including me) will continue to buy, store and cherish books. Probably moreso than we did before with the (perhaps Google-supplied, perhaps not) ability to find books we'd never have come across otherwise.

The thing with Google is this: it is a means of access to information and a powerful one. They are not without competitors, and they will probably never be without competitors. They are never going to be the one entity that absolutely dominates everything on the web. And anything they propose to do is can probably be duplicated by one of their competitors. Google isn't the millennium, it's just a good search tool.

Copyright holders who deny the fair use of their material (let's leave the legal nitpicking aside here and just say that searchability and the display of excerpts is fair: it will cause few or no loss of sales (actually quite the opposite) and will certainly lend to the propagation of knowledge), with few exceptions are slitting their own throats. Because the big threat to books isn't being digitized. It's not being digitized.

There is an incrediblee wealth of knowledge now in print, but not available for search. And that fact will make the world of print increasinglyy the domain of odd ducks like me. While this might make people like me more special, if you are truly interested in books, you'll be more supportive of the reasonably regulated digitizing of print.

OPK

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Interlochen Backs Out

Interlochen backs out

TOM CARR

and VANESSA McCRAY

Record-Eagle staff writers

Photo: Record-Eagle/Tyler Sipe

Interlochen Center for the Arts no longer plans to run the State Theatre in downtown Traverse City.TRAVERSE CITY - Interlochen Center for the Arts no longer plans to run the State Theatre as a performance place, and several groups are negotiating the future of the historic movie house.

The front-runner could be the Traverse City Film Festival. The State was the marquee venue last summer for the first film festival. It budgeted $1 million next year for the "purchase, operation or renovation" of the Front Street theater, according to festival co-founder Doug Stanton.

"That would be our hope, but negotiations are ongoing, and we just need to be positive," Stanton said.

The State currently is owned by the nonprofit State Theatre Group, which in 2003 announced a partnership with Interlochen. The plan was to raise $6.5 million in 12 months to upgrade the theater to allow for many types of entertainment and live performances.

The funding hasn't materialized and Interlochen backed away from its plan to run it once renovated.

"It appears to us the resources to create the multiple-use performing arts center and the momentum for that do not exist at this time," Interlochen spokesman Paul Heaton said.

Interlochen is still involved in planning for the theater's future and hopes to use it for some performances, Heaton said.

The State Theatre Group, Interlochen, Rotary Charities of Traverse City, the film festival and the Traverse Symphony Orchestra are among those discussing what's next.

"We are all talking and trying to figure out what is going to work best," said Marsha Smith, Rotary's executive director.

The orchestra hoped to make the theater its new home if the full plan had been instituted.

The orchestra board hasn't ruled it out, but Interlochen's diminished involvement "has resulted in a reassessment that is ongoing," TSO spokesman Andy Buelow said.

State Theatre Group chairman Charles Judson said the owners are trying to "put together a plan" and won't actively fundraise until it does. The group is out of cash, Smith said.

"Everybody is being very cooperative," Judson said. "We definitely want there to be a future for it. We're trying to reach a shared vision."

Rotary gave $750,000 in grants to the State project to date, said Smith. It holds a $250,000 lien on the building.

City records placed a $670,000 value on the theater and the property in 1996. It has not been assessed since then because of its nonprofit status.

Film festival spokeswoman Tracy Kurtz said the festival invested more than $250,000 in donated materials and labor to spruce up the theater for the festival's inaugural run.

The festival envisions using the State to show movies, host concerts and provide a venue for other arts groups, Stanton said.

"The theater can be an incredibly attractive magnet for downtown and benefit the entire community," he said.

The festival's plans for the theater are "simple, small and local," he added.

"We are really excited about the opportunity to preserve this important downtown landmark," Stanton said.

I must be psychic!

Seriously, though, this is for the best. Interlochen doesn't have what it takes to make the State the sort of grassroots, hip, funky, more-with-less operation. The

The film festival on the other hand has some promise as a platform on which other community groups might put together a program (or programs) that will both bring the people in and give them something that goes beyond standard issue high culture.

OPK

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Michael Moore to Buy TC's State Theater?

Some time back I wrote this about Moore and the State Theater:

In 1996, plans were announced to convert the theater and the former Kurtz Music building next door into a $6.9 million community arts and performance complex.

A legal dispute between the State Theatre Group and Barry Cole, who donated the building to the group, held up the project and it was scaled back to $4.6 million before it again stalled.

In 2003, the State Theatre Group and Interlochen Center for the Arts announced a partnership to renovate it. [Interlochen's contribution being . . . no cash whatsoever and two years of nothing much happening.]

The group has about $6.5 million yet to raise for the $10 million renovation, Interlochen spokesman Paul Heaton said. [The preceding from the TC Record-Eagle. ]

Back in 2003 the big excitement was that the Interlochen Arts Academy was partnering with the Sate Theater group to get this project rolling.

Two years and nothing happened until Michael Moore came along.

One has to wonder what's going on with the people supposedly in charge of this potentially quite valuable space. Why is the famously self-serving Interlochen now being given power over the space when they refuse to invest any money in it and seem to have so little power to re-invigorate the project.

Why does TC think that having an Interlochen outpost in town is such a grand thing for the city (as opposed to Interlochen itself)? Aside from providing a home for the Symphony Orchestra--which I and the vast majority of area residents have zero interest in--what is the vision for this place? How can it be made to be a community resource aside from handing it over (for nothing!) to an Arts academy that has never shown any real interest in the local community.

Perhaps we ought to consider turning the thing over to Moore, who has an equal reputation for being self-serving, but who can at least get some things done.Well, it seems that there's to be an announcement of an "acquisition" by the Traverse City Film Festival (otherwise known as Michael Moore) tomorrow morning.

I'm betting they bought the State. And I'm hoping that this will end Interlochen's tie to the theatre, as well. Interlochen booking the State Theatre is no blessing: just look at how unimaginative their own festival booking has been over the past several years. An Interlochen logowear store is no blessing to the State Theatre. And effectively selling tickets doesn't take genius, it just takes the promise of profit.

A film-festival-led effort to completely take over this facility, though, could be a wonderful thing for the community. Imagine this facility with strong links to a wide-range of local and grassroots organizations through town: the food co-op, churches, political organizations, the community radio station, TCTV 2, the library, 54-40 or Fight, the locally-owned bookstore . . .

This could really be something if Moore is willing to risk his prospects of getting into Traverse City's Rotary Club (seriously, he really seems to want to learn the TC secret handshake!).

OPK

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Sex or Death?

A Traverse City area physician (Dr. Meg Meeker) was at the forefront of bringing the HPV virus to public attention, which was a good thing. However, Dr. Meeker persistently overstated the risks the virus posed, and I always strongly suspected that her real objective was to discourage pre-marital sex, and that she secretly looked upon HPV as a heaven-sent stratagem to keep people from having sex for the fun of it.

Well, I haven't heard what Meeker thinks, but other conservatives definitely seem less than thrilled with the recent development of an HPV vaccine. So concerned are they for the moral purity of our womanhood, they'd rather they die of cancer than send a subtle message that sex is OK.

I think if Meeker is really just the concerned doctor she tries to pass herself off as, she'll condemn these heartless prudes in no uncertain terms.

Cervical Cancer Vaccine Gets Injected With a Social IssueOPK

Some Fear a Shot For Teens Could Encourage Sex

By Rob Stein

Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, October 31, 2005; A03

A new vaccine that protects against cervical cancer has set up a clash between health advocates who want to use the shots aggressively to prevent thousands of malignancies and social conservatives who say immunizing teenagers could encourage sexual activity.

Although the vaccine will not become available until next year at the earliest, activists on both sides have begun maneuvering to influence how widely the immunizations will be employed.

Groups working to reduce the toll of the cancer are eagerly awaiting the vaccine and want it to become part of the standard roster of shots that children, especially girls, receive just before puberty.

Because the vaccine protects against a sexually transmitted virus, many conservatives oppose making it mandatory, citing fears that it could send a subtle message condoning sexual activity before marriage. Several leading groups that promote abstinence are meeting this week to formulate official policies on the vaccine.

In the hopes of heading off a confrontation, officials from the companies developing the shots -- Merck & Co. and GlaxoSmithKline -- have been meeting with advocacy groups to try to assuage their concerns.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Local Currency

The following guest editorial just appeared in the local paper:

Bay Bucks is one truly bad idea

By WARREN CLINE

In the Record Eagle's Oct. 16 edition, the community was introduced to the concept of "Bay Bucks." The idea of Bay Bucks is to circulate a local currency in competition with the U.S. dollar that is only accepted by local merchants and force the holders of Bay Bucks to buy locally. While encouraging local citizens to buy from local merchants is a great goal, using Bay Bucks is a bad idea.

The United States government and the U.S. Department of Treasury devote considerable efforts to fight the counterfeiting of the U.S. dollar.

Hold up a $20 bill to the light and notice all of the measures used to fight counterfeiting. U.S. Treasury agents hunt down counterfeiters and throw them in jail. Any high school student with a color copier can counterfeit Bay Bucks! Will any law enforcement agency stop the counterfeiting of Bay Bucks?

As a consumer, if you own Bay Bucks you cannot use them to pay federal taxes, Michigan taxes or local property taxes. You can't pay mortgage payments, car payments, credit card payments, insurance payments, utility bills or rent payments. No major grocery store or gas station accepts Bay Bucks, so you can't buy groceries or gasoline. You can't deposit Bay Bucks into your checking account.

Bay Bucks will be a burden, not a benefit, to local merchants. The accounting systems of local merchants are not designed to process an alternative currency.

The typical local merchant deposits his currency receipts into his bank account every day. Then the merchant uses his bank account to pay employees, suppliers, landlords, etc.

Any local business collecting Bay Bucks will have to set aside that currency and then look for suppliers who are willing to accept the Bay Bucks currency. Warning: If you own a local business, don't agree to accept Bay Bucks until after you speak to your CPA or accountant about the cost and risk of accepting Bay Bucks.

If a local currency helped local businesses, every state in the union would issue its own currency. All of us in America benefit from having one currency, protected by the power of the United States of America.

None of the respected local institutions have endorsed Bay Bucks. There is no regulation by local government. There is no endorsement by the Chamber of Commerce. There is no clearinghouse by local banks.

The promoters of Bay Bucks will go into our community and sell these nearly useless pieces of paper to our citizens in exchange for real U.S. currency. What a deal! What are they going to do with the real money?

If we want to support local merchants (and we should) then we should buy their products and services with real U.S. dollars and we should give the waiters and waitresses real money, not pretend money, when we leave a tip.

Bay Bucks is a bad idea.

Now, I am far from thinking that Bay Bucks are going to have a huge positive impact on Northern Michigan, but Cline really ought to get his facts straight before sounding off on Bay Bucks.

For one thing: US currency has, up until very recently been widely reputed to be the most easily counterfeited in the world. I have both a ten and a twenty in my pocket right now that have zero security measures visible when I hold them up to the light.

Can any high school student make a color copy of a Bay Buck? Sure. But that student can just as well make a copy of a US twenty. And have just as much chance of getting away with passing it.

Bay Bucks DO include a number of security provisions, including being made of high quality paper, being difficult for color copiers to scan, and having a watermark. One wonders if Mr. Cline actually looked at a Bay Buck before writing his screed.

As for local businesses accepting the currency: there are, of course, considerations and provisions to be made in accepting an alternative currency. No one says otherwise.

As far as "respected local institutions go." Well, all local business are free to choose whether they want to take on the second currency in order to help out a local initiative. And Oryana Food Coop has chosen to do so. And amongst the folks likely to be interested in Bay Bucks, there's probably no more respected and heavily patronized business than that. I don't think anyone really cares whether Mr. Cline thinks the Bay Bucks buyers and sellers are a bunch of rabble. If Cline doesn't like Bay Bucks, he can decline to accept them and continue to congratulate himself on his irreproachable respectability.